Field Tested & Hunter Approved

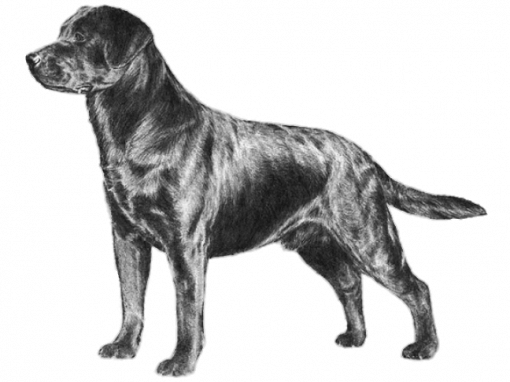

Labrador Retriever Breed Standard

(From The Labrador Retriever, Inc. effective March 31, 1994)

General Appearance

The Labrador Retriever is a strongly built, medium-sized, short-coupled, dog possessing a sound, athletic, well-balanced conformation that enables it to function as a retrieving gun dog; the substance and soundness to hunt waterfowl or upland game for long hours under difficult conditions; the character and quality to win in the show ring; and the temperament to be a family companion.

Physical features and mental characteristics should denote a dog bred to perform as an efficient Retriever of game with a stable temperament suitable for a variety of pursuits beyond the hunting environment. The most distinguishing characteristics of the Labrador Retriever are its short, dense, weather resistant coat; an “otter” tail; a clean-cut head with broad back skull and moderate stop; powerful jaws; and its “kind” friendly eyes, expressing character, intelligence and good temperament.

Above all, a Labrador Retriever must be well balanced, enabling it to move in the show ring or work in the field with little or no effort. The typical Labrador possesses style and quality without over refinement, and substance without lumber or cloddiness. The Labrador is bred primarily as a working gun dog; structure and soundness are of great importance.

Size, Proportion and Substance

- Size – The height at the withers for a dog is 22-1/2 to 24-1/2 inches; for a bitch is 21-1/2 to 23-1/2 inches. Any variance greater than 1/2 inch above or below these heights is a disqualification. Approximate weight of dogs and bitches in working condition: dogs 65 to 80 pounds; bitches 55 to 70 pounds. The minimum height ranges set forth in the paragraph above shall not apply to dogs or bitches under twelve months of age.

- Proportion – Short-coupled; length from the point of the shoulder to the point of the rump is equal to or slightly longer than the distance from the withers to the ground. Distance from the elbow to the ground should be equal to one half of the height at the withers. The brisket should extend to the elbows, but not perceptibly deeper. The body must be of sufficient length to permit a straight, free and efficient stride; but the dog should never appear low and long or tall and leggy in outline.

- Substance – Substance and bone proportionate to the overall dog. Light,”weedy” individuals are definitely incorrect; equally objectionable are cloddy lumbering specimens. Labrador Retrievers shall be shown in working condition, well-muscled and without excess fat.

Head

- Skull – The skull should be wide; well developed but without exaggeration. The skull and foreface should be on parallel planes and of approximately equal length. There should be a moderate stop-the brow slightly pronounced so that the skull is not absolutely in a straight line with the nose. The brow ridges aid in defining the stop. The head should be clean-cut and free from fleshy cheeks; the bony structure of the skull chiseled beneath the eye with no prominence in the cheek. The skull may show some median line; the occipital bone is not conspicuous in mature dogs. Lips should not be squared off or pendulous, but fall away in a curve toward the throat. A wedge-shape head, or a head long and narrow in muzzle and back skull is incorrect as are massive, cheeky heads. The jaws are powerful and free from snippiness

- Nose – The nose should be wide and the nostrils well-developed. The nose should be black, on black or yellow dogs, and brown on chocolates. Nose color fading to a lighter shade is not a fault. A thoroughly pink nose or one lacking in any pigment is a disqualification.

- Teeth – The teeth should be strong and regular with a scissors bite; the lower teeth just behind, but touching the inner side of the upper incisors. A level bite is acceptable, but not desirable. Undershot, overshot, or misaligned teeth are serious faults. Full dentition is preferred. Missing molars or pre-molars are serious faults.

- Ears – The ears should hang moderately close to the head, set rather far back, and somewhat low on the skull; slightly above eye level. Ears should not be large and heavy, but in proportion with the skull and reach to the inside of the eye when pulled forward.

- Eyes – Kind, friendly eyes imparting good temperament, intelligence and alertness are a hallmark of the breed. They should be of medium size, set well apart, and neither protruding nor deep set. Eye color should be brown in black and yellow Labradors, and brown or hazel in chocolates. Black, or yellow eyes give a harsh expression and are undesirable. Small eyes, set close together or round prominent eyes are not typical of the breed. Eye rims are black in black and yellow Labradors; and brown in chocolates. Eye rims without pigmentation is a disqualification.

Neck, Top Line and Body

- Neck – The neck should be of proper length to allow the dog to retrieve game easily. It should be muscular and free from throatiness. The neck should rise strongly from the shoulders with a moderate arch. A short, thick neck or a “ewe” neck is incorrect.

- Top Line – The back is strong and the top line is level from the withers to the croup when standing or moving. However, the loin should show evidence of flexibility for athletic endeavor.

- Body – The Labrador should be short-coupled, with good spring of ribs tapering to a moderately wide chest. The Labrador should not be narrow chested; giving the appearance of hollowness between the front legs, nor should it have a wide spreading, bulldog-like front. Correct chest conformation will result in tapering between the front legs that allows unrestricted forelimb movement. Chest breadth that is either too wide or too narrow for efficient movement and stamina is incorrect. Slab-sided individuals are not typical of the breed; equally objectionable are rotund or barrel chested specimens. The underline is almost straight, with little or no tuck-up in mature animals. Loins should be short, wide and strong; extending to well developed, powerful hindquarters. When viewed from the side, the Labrador Retriever shows a well-developed, but not exaggerated fore chest.

- Tail -The tail is a distinguishing feature of the breed. It should be very thick at the base, gradually tapering toward the tip, of medium length, and extending no longer than to the hock. The tail should be free from feathering and clothed thickly all around with the Labrador’s short, dense coat, thus having that peculiar rounded appearance that has been described as the “otter” tail. The tail should follow the topline in repose or when in motion. It may be carried gaily, but should not curl over the back. Extremely short tails or long thin tails are serious faults. The tail completes the balance of the Labrador by giving it a flowing line from the top of the head to the tip of the tail. Docking or otherwise altering the length or natural carriage of the tail is a disqualification.

Forequarters

Forequarters should be muscular, well coordinated and balanced with the hindquarters.

- Shoulders – The shoulders are well laid-back, long and sloping, forming an angle with the upper arm of approximately 90 degrees that permits the dog to move his forelegs in an easy manner with strong forward reach. Ideally, the length of the shoulder blade should equal the length of the upper arm. Straight shoulder blades, short upper arms or heavily muscled or loaded shoulders, all restricting free movement, are incorrect.

- Front Legs – When viewed from the front, the legs should be straight with good strong bone. Too much bone is as undesirable as too little bone, and short legged, heavy boned individuals are not typical of the breed. Viewed from the side, the elbows should be directly under the withers, and the front legs should be perpendicular to the ground and well under the body. The elbows should be close to the ribs without looseness. Tied-in elbows or being “out at the elbows” interfere with free movement and are serious faults. Pasterns should be strong and short and should slope slightly from the perpendicular line of the leg. Feet are strong and compact, with well-arched toes and well-developed pads. Dew claws may be removed. Splayed feet, hare feet, knuckling over, or feet turning in or out are serious faults.

Hindquarters

The Labrador’s hindquarters are broad, muscular and well-developed from the hip to the hock with well-turned stifles and strong short hocks. Viewed from the rear, the hind legs are straight and parallel. Viewed from the side, the angulation of the rear legs is in balance with the front. The hind legs are strongly boned, muscled with moderate angulation at the stifle, and powerful, clearly defined thighs. The stifle is strong and there is no slippage of the patellae while in motion or when standing. The hock joints are strong, well let down and do not slip or hyper-extend while in motion or when standing. Angulation of both stifle and hock joint is such as to achieve the optimal balance of drive and traction. When standing the rear toes are only slightly behind the point of the rump. Over angulation produces a sloping topline not typical of the breed. Feet are strong and compact, with well-arched toes and well-developed pads. Cow-hocks, spread hocks, sickle hocks and over-angulation are serious structural defects and are to be faulted.

Coat

The coat is a distinctive feature of the Labrador Retriever. It should be short, straight and very dense, giving a fairly hard feeling to the hand. The Labrador should have a soft, weather-resistant undercoat that provides protection from water, cold and all types of ground cover A slight wave down the back is permissible. Woolly coats, soft silky coats, and sparse slick coats are not typical of the breed, and should be severely penalized.

Color

The Labrador Retriever coat colors are black, yellow and chocolate. Any other color or a combination of colors is a disqualification. A small white spot on the chest is permissible, but not desirable. White hairs from aging or scarring are not to be misinterpreted as brindling.

- Black – Blacks are all black. A black with brindle markings or a black with tan markings is a disqualification.

- Yellow – Yellows may range in color from fox-red to light cream, with variations in shading on the ears, back, and underparts of the dog.

- Chocolate – Chocolates can vary in shade from light to dark chocolate. Chocolate with brindle or tan markings is a disqualification.

Movement

Movement of the Labrador Retriever should be free and effortless. When watching a dog move toward oneself, there should be no sign of elbows out. Rather, the elbows should be held neatly to the body with the legs not too close together. Moving straight forward without pacing or weaving, the legs should form straight lines, with all parts moving in the same plane. Upon viewing the dog from the rear, one should have the impression that the hind legs move as nearly as possible in a parallel line with the front legs. The hocks should do their full share of the work, flexing well, giving the appearance of power and strength. When viewed from the side, the shoulders should move freely and effortlessly, and the foreleg should reach forward close to the ground with extension. A short, choppy movement or high knee action indicates a straight shoulder; paddling indicates long, weak pasterns; and a short, stilted rear gait indicates a straight rear assembly; all are serious faults. Movement faults interfering with performance including weaving; side-winding; crossing over; high knee action; paddling; and short, choppy movement, should be severely penalized.

Temperament

True Labrador Retriever temperament is as much a hallmark of the breed as the “otter” tail. The ideal disposition is one of a kindly, outgoing, tractable nature; eager to please and non-aggressive towards man or animal. The Labrador has much that appeals to people; his gentle ways, intelligence and adaptability make him an ideal dog. Aggressiveness towards humans or other animals, or any evidence of shyness in an adult should be severely penalized.

Disqualifications

- Any deviation from the height prescribed in the Standard.

- A thoroughly pink nose or one lacking in any pigment.

- Eye rims without pigment.

- Docking or otherwise altering the length or natural carriage of the tail.

- Any other color or a combination of colors other than black, yellow or chocolate as described in the Standard.

- February 12, 1994 – Effective March 31, 1994

Breed History

The Labrador Retriever was developed in England in the mid 1800s by a handful of private kennels dedicated to developing and refining the perfect gundog. That many such kennels were pursuing their own vision of such a dog is the reason behind the variety of today’s retriever breeds.

Early Ancestors

It’s fairly clear that there were no indigenous dogs in Newfoundland when the first fishing companies arrived. If the native Americans of the time had any, the explorers never observed them. Thus it’s quite likely that the St. Johns dogs themselves come from old English Water Dog breeds, insofar as fishermen were the primary people on Newfoundland for centuries. There is also some speculation that the old St. Hubert’s dog might have been brought over as well — illustrations of the breed show a black, drop-eared dog with a certain resemblance to the Labrador. But it is unknown if the fishermen going to Newfoundland would have had hound dogs used for game rather than water dogs.

We can only speculate what happened, but we do know that the cod fishermen sent out from Britain practiced “shore fishing.” Small dories were used for the actual fishing, and they worked in teams of four — two in the boat and two on the shore to prepare and cure the fish. They would have needed a small dog to get in and out of the boat, with a short water repellent coat so as not to bring all the water into to the boats with them. They would have bred for a strong retrieving instinct to help retrieve fish and swimming lines, and a high degree of endurance to work long hours. If the runs were heavy, the fishermen were reputed to go for as long as twenty hours to haul the fish in.

The dog developed for this early work could be found in several varieties: a smaller one for the fishing boats, and a larger one with a heavier coat for drafting. The smaller dog has been called, variously, the Lesser St. John’s dog, the Lesser Newfoundland, or even the Labrador. These dogs came from Newfoundland; it is unknown why the name “Labrador” was chosen except possibly through geographical confusion. Charles Eley, in History of Retrievers at the end of the 19th century comments:

The story was that the first Labrador to reach England swam ashore from vessels which brought cod from Newfoundland It was claimed for them that their maritime existence had resulted in webbed feet, a coat impervious to water like that of an otter, and a short, thick ‘swordlike’ tail, with which to steer

safely their stoutly made frames amid the breakers of the ocean.

Part of the confusion over the names is that “St. John’s dog” and “Newfoundland dog” were used interchangeably for both the greater (larger) and lesser (smaller) varieties. And the term Labrador has also been used to refer to the lesser St. John’s dog, especially in the latter half of the 19th century. The greater is commonly held to be the direct ancestor of today’s Newfoundland, while the lesser was used to develop many of the retrieving breeds, including today’s

Labrador.

The exact relationship between the two varieties of the St. Johns dog (and some 19th century writers listed up to four varieties) is also unclear; we don’t know which came first, or to what degree they were related. Certainly the greater St. Johns dog was first imported to England nearly a hundred years earlier, and many contemporary and modern day writers assume that the lesser was developed from the greater but we have no real evidence one way or another. Newfoundland has been used for fishing and other activities since approximately 1450 so there has been plenty of time for the development of the St. Johns dog and its varieties.

Development in England

From the time these dogs were first imported back to England in the early 1800s to 1885 when the combined effects of Newfoundland’s Sheep Act and Britain’s Quarantine Act shut down further importation, a handful of kennels regularly imported lesser St. Johns dogs and carefully bred them for gun dog work on their estates. These kennels include those of Buccleuch and Malmesbury, each of which imported lesser St. John’s dogs throughout the 19th century for their private lines.

The second Earl of Malmesbury (1778-1841) and his son the third Earl (1807-1889) imported the dogs and kept their lines going until the third Earl’s death. In a letter he wrote in about 1887 he noted:

“We always called mine Labrador dogs and I have kept the breed as pure as I could from the first I had from Poole, at that time carrying on a brisk trade with Newfoundland. The real breed may be known by their having a close coat which turns the water off like oil, above all, a tail like an otter.”

At about the same time, the fifth Duke of Buccleuch (1806-1884), his brother Lord John Scott (1809-1860) and the tenth Earl of Home (1769-1841) embarked on a similar but independent program. They lived within a 30 mile radius and developed the Buccleuch line. The eleventh Lord of Home (1799-1881) continued his dogs, but the line was nearly extinct about the time of his death.

However, a chance meeting between the third Earl of Malmesbury and the sixth Duke of Buccleuch and the twelfth Earl of Home resulted in the older Malmesbury giving the two young Lords some of the dogs from his lines. From these dogs, given in 1882, the Buccleuch line was revitalized and the breed carried into the 20th century. Buccleuch’s Ned and Buccleuch’s Avon are generally agreed upon as being the ancestors of all Labradors.

That two different kennels, breeding independently for at least 50 years, had such similar dogs argues that the Labrador was kept very close to the original St. John’s breed. Thus it is probable that today’s Labrador, of all the modern retrievers, is the most closely related to the original St. John’s dog and by extension, as closely related to the modern Newfoundland as to the other retriever breeds such as Golden Retrievers, Flat Coat Retrievers, etc.

The Twentieth Century

By the turn of the century, these retrievers were appearing in the British Kennel Club’s events. At this point, retrievers from the same litter could wind up being registered as different retrievers. The initial category of “Retrievers” included curly coats, flat coats, liver-colored retrievers and the Norfolk retriever (now extinct). As types became fixed, separate breeds were created for each and the Labrador Retriever finally gained its separate registration under the Kennel Club in 1903.

While there have been strains of Labradors bred pure up to this time, it is unknown how many of these cross-bred dogs were folded into “Labradors” or into other breeds as the registrations began to separate. Many breeders feel that crossbreeding at this time accounts for much of the poor type that can appear today; however claims about the use of Pointers or Rottweilers can probably be safely discounted.

The first two decades in the 20th century saw the formation in Britain of some of the most influential kennels that provided the basis for the breed as we know it today. Lord Knutsford’s Munden Labradors, and Lady Howe’s Banchory Labradors are among several. At this time, many dogs distinguished themselves in both field trials and conformation shows; the high number of Dual Champions at this time attests to the breed’s versatility.

Labradors were first imported to the United States during World War I. At this point, the AKC still classified them as “Retrievers;” it was not until the late 1920’s that the retrievers were split up into the breeds we know today in the AKC. The Labrador Retriever has been used heavily in the US as a gundog; the American Labrador Retriever Club, Inc. (LRC, Inc), is to this day primarily a field trial organization, and it was instrumental in forming the AKC field trials.

The two World Wars greatly diminished the breed in numbers (as it did many others). After the second World War saw the rise of the Labrador Retriever in the United States, where Britain’s Sandylands kennel through imports going back to Eng CH Sandyland’s Mark influenced the shape and direction the show lines took in this country. Other influential dogs include American Dual CH Shed of Arden, a grandson of English Dual CH Banchory Bolo, especially evident in field trial lines.

This return trip to the Americas resulted in the widely expanded use of the Labrador as a gun dog. In Britain, the Labrador was, and still is, used primarily for upland game hunting, often organized as a driven bird shoot. Typically, separate breeds were used for different tasks; and the Labrador was strictly for marking the fall, tracking and retrieving the game. But in the United States and Canada, the breed’s excellence at waterfowl work and game finding became apparent and the Labrador soon proved himself adaptable to the wider and rougher range of hunting conditions available. The differences between British and American field trials are particularly illustrative.

Copyright © 1992-2004 by Liza Lee Miller and Cindy Tittle Moore. All rights reserved.

Breed Type

American versus English or Conformation/Show versus Field

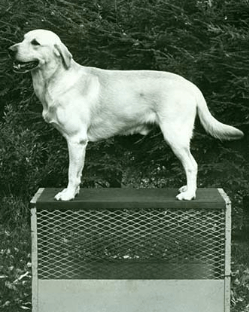

The Labrador Retriever Club, Inc.’s position is, there is only one breed of dog known as the Labrador Retriever, described by the Standard of the Breed. Within Labrador Retriever breed type there are variations in body style which have evolved to suit the use of the dog, as well as the preferences of individual breeders and owners.

In the United States the general public has begun to label these variations mistakenly as “English or “American” style. Perhaps a better description for variations in style is “Show/Conformation” or “Field” styles.

The Field or “American” style of dog is the label often attached to a Labrador Retriever possessing lighter bone structure and exhibiting more length of leg, a less dense coat, and a narrower head with more length of muzzle.

The Conformation/Show or “English” style Labrador Retriever is generally thought of as a stockier dog, heavier of bone and shorter on leg and with a denser coat, and having a head often described as “square or blocky.” However, working/field variations occur in England as well, so this description is not necessarily suitable.

These general images portray the extremes of both styles and do not help to identify the temperament, train-ability or health of the dog. In fact, the vast majority of Labrador Retrievers, whether of Conformation/Show breeding or Field breeding, possess moderate body styles much closer to the written Standard of the breed. It is possible that within a single litter, whether that litter has been bred for Show/Conformation or Field, individual pups can mature to be representatives of the range, though rarely producing the extremes, of the two styles.

We recommend that you discuss the issue of size and style, as well as temperament, train-ability and health, with any breeder you contact. However, please remember that there is only one Labrador Retriever breed, one that meets the requirements as set forth in the Official Standard.

Information & Resources